Ajay was a collector of miniature trinkets. Every Saturday, he wandered the street fairs along the Upper West Side, searching for something unusual. One morning, something caught his eye. Tucked between a signed Derek Jeter baseball and a crate of sun-faded LPs was an unmarked velvet pouch, musty with the scent of dust. Inside it rested an impossibly detailed six-inch skyscraper.

It resembled the Empire State Building but wasn’t quite: its spire narrower, its setbacks steeper, its symmetry slightly off. Its doors bore logos that Ajay didn’t recognize. The windows, though no bigger than sesame seeds, caught the light in a way that made Ajay squint—because, if he stared long enough, he could almost see movement inside.

Ajay was twelve, a straight-A student who read three grade levels ahead but struggled to speak up in class. He lived in a world of busy parents and preteen isolation. His mother, Professor Sharma, spoke in clipped English about postcolonial theory and American hegemony, her brow knitting in worry over a country that preached equality but whispered prejudice. She published papers on displacement while barely noticing her son's quiet dislocation.

His father, a scholar of foreign policy, tapped at his laptop in the living room, groaning about Senate debates and the half-truths politicians peddled. They—two brilliant souls from Mumbai, India, who had come to Columbia University for its prestige—had little time for bedtime stories or interpreting their son's silent glances. At faculty dinners, they praised Ajay's intelligence to colleagues, but at home, they assumed his silence meant contentment.

So Ajay had turned, as he always did, to his miniature world: tin soldiers plucked from flea markets, plastic dancers from birthday cake toppers, and matchstick replicas of the Brooklyn Bridge. In his bedroom, these little souls listened to what his parents never heard.

That Saturday morning, Ajay brought home the tiny high-rise he’d purchased for seven dollars and set it on his desk, where, beneath the lamp’s glow, its windows shimmered alive—soft oranges and faint blues, an eternal twilight dancing inside walls no bigger than his thumbnail.

This is impossible, he told himself, as the rational part of his mind—the part that earned him gold stars and teacher praise—rebelled against what he saw. Buildings didn't have lights. Toys didn't breathe. But his eyes betrayed his logic.

He told his parents that night, approaching them in the kitchen where they debated immigration policy over reheated takeout.

“There are lights in my building,” he said.

His mother glanced up from her laptop. “What building, beta?”

“The one I bought today. I think there are people inside.”

His father looked up from his tablet and smiled. “People? What kind of people?”

“Little people. Obviously.”

“Obviously,” his father repeated, amused. “Sometimes little people have big problems—especially if they’re trying to run a democracy.”

Ajay shrugged. “I guess.”

“Speaking in the abstract, of course,” his father leaned back and smiled. “You’re not running a refugee camp, are you?”

“No.”

“Good,” his father said, already turning back to his screen. “Give the little people what they want.”

“They’re not real, Amit,” his mother said with a smile.

His father glanced at Ajay. “I didn’t say they were. Are they real, Ajay?”

Ajay hesitated. “No. Maybe not.”

“Well then, problem solved,” his father said lightly.

And just like that, they returned to their screens, typing through the next article, the next panel discussion about belonging and displacement.

That night, in the adjoining rooms, they argued quietly:

“Look at how free this country pretends to be,” his mother hissed. “It’s hell, Amit—every other day another policy, another deportation.”

“It’s the same in some parts of India now,” his father replied. “But here—never in my wildest dreams did I imagine academics would have to choose their words so carefully.”

Ajay pressed himself against the wall, the tension making the air thrum. Outside his window, New York sprawled in all directions—millions of lights, millions of people, all of them strangers. He felt suspended between his parents’ world of theories and a reality that seemed to shift with each blink.

He stepped back, returning to his desk where the skyscraper now stood nearly a foot tall. It had grown in his absence.

No, he thought. Things don't grow. Not like this.

But inside the highest windows, a faint silhouette had appeared: a person, or something that looked like one, curled against the glass, their head tilted back in a silent scream. At the base, he heard it: a sound like "Eeeek," so small and broken it might have been chalk on a blackboard. He felt his chest twist.

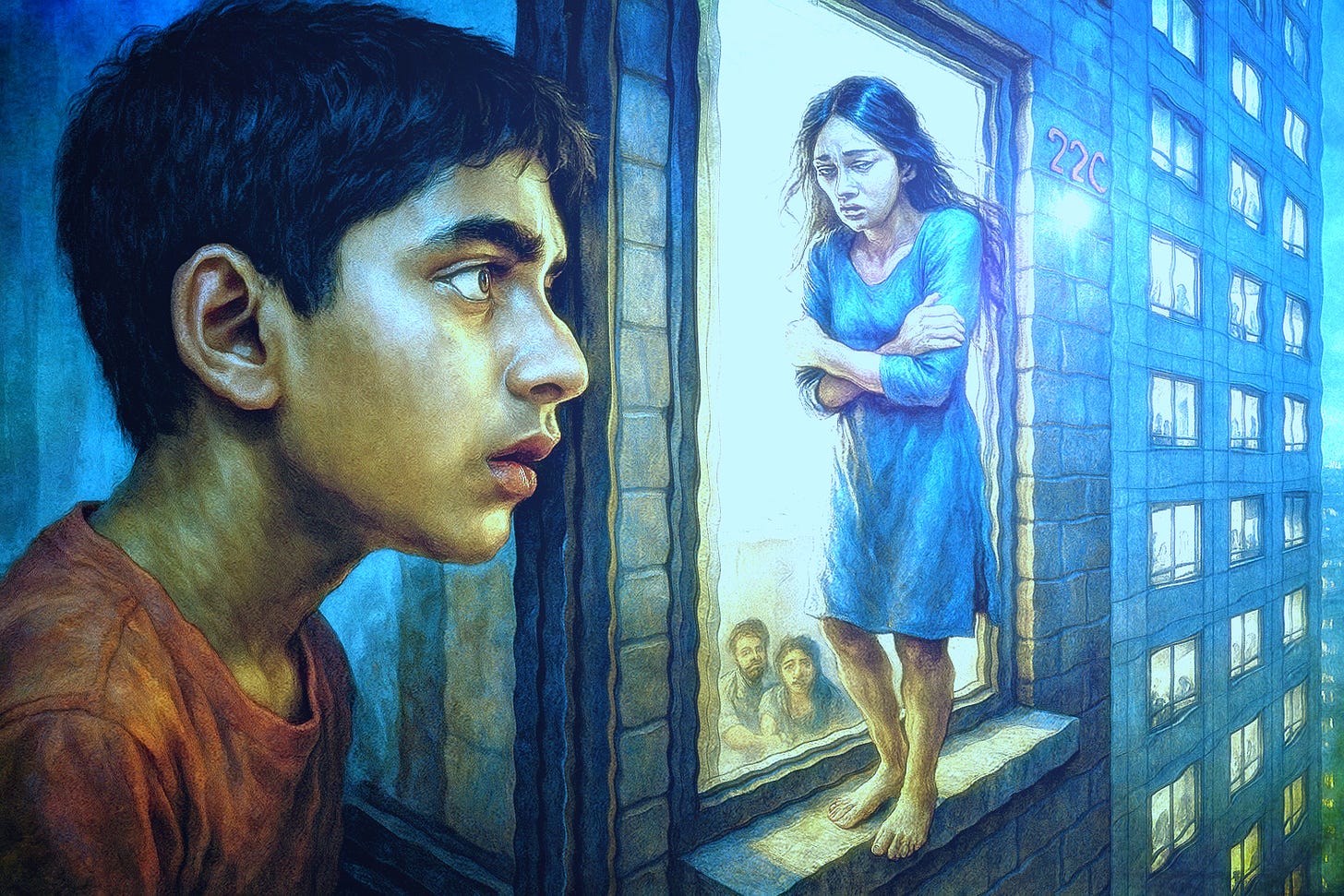

By the next morning, the building stood nearly eighteen inches tall. The figure in the window was easier to see now—a woman, or something like one, holding her arms tightly across her chest, as if cold or afraid.

At breakfast, his parents hurried through their routines, flipping through notes and sipping coffee as they discussed their morning lectures. Ajay tried again.

“My building is getting bigger,” he said.

His mother paused, cup halfway to her lips. “What did you say?”

“The skyscraper. It’s growing.”

She studied him then, really looked, for the first time in weeks. “Are you feeling alright? You seem pale.”

“I’m fine. But the building—”

“We need to talk about moving,” his father interrupted gently, stacking his notes. “There’s an apartment closer to campus. It’ll mean a shorter commute for both of us.”

Ajay nodded.

He began to question whether reality was as fixed as his parents claimed. Their world—lectures, papers, policy—depended on proof. But Ajay was starting to believe in things that couldn’t be cited.

The skyscraper continued to grow. Two feet. Then three. He stopped going outside. Meals went untouched. His schoolbooks sat unopened. He watched the building more than he watched anything else.

Its walls filled with life: kitchens with ticking clocks, stairwells lit by flickering bulbs, elevators that stalled halfway between floors. On the twenty-second floor, a woman walked back and forth, as if waiting for someone—or something-to set her free.

The city outside seemed to mock him. From his window, he could see the real skyscrapers—solid, predictable, filled with people who belonged somewhere. But his building was different. It was alive, and it was his.

"You must be the new owner?" a voice came from within.

Ajay jumped back. A little man! I'm losing my mind, he thought.

A small, rotund man, around 50 years old, appeared on the first floor. "I'm the superintendent. Name's Nunzio. You the new owner?"

“ I-I think I'm imagining you," Ajay stammered.

"Kid, you bought the building. I work here. What's to imagine? Though I gotta say, you're young for a property owner. You one of those crypto-millionaires?"

"I'm twelve."

"Figures. Well, twelve or not, we got problems. Squatters on the fourteenth floor. You're going to have to obtain a court order and forcibly remove them.”

“Oh, and the boiler’s shot—no heat half the time. And there's a woman in 22C who wants to throw herself out the window every Saturday night. Did they tell you this when you bought the building?"

"No one told me anything. I bought it for seven dollars."

"Seven million? You got a good deal. Listen, I don't care if you're having some kind of breakdown, but I got a building to keep up here. So let's communicate. What'd you say your name was again?"

"Ajay."

"Nice to meet you, Mr. Ajay,” Nunzio said, tipping his cap.

Ajay stood frozen. His hands tingled as if he’d touched something electric. He considered running to tell his parents about the little man named Nunzio, about the boiler, about the woman in 22C—but stopped himself. They wouldn’t understand.

He turned back to the building. The lights on the twenty-second floor pulsed faintly. The woman Nunzio mentioned. The one that he said threatened to throw herself out of the window. She had to be the one he’d seen earlier—the woman with the sad eyes and the curled posture. He scanned the windows, searching for her.

But something else caught his attention.

On the fourteenth floor, a man stood by a broken window, wild-eyed, coat threadbare. He leaned out, waving his arms at Ajay.

“Hey, you can’t evict us! We got squatter’s rights. Just because we can’t afford to pay rent don’t mean we’re not human beings!”

Ajay blinked. “I—I wasn’t going to evict anyone.”

The man pointed an accusatory finger. “Nunzio said you were the new owner. That true?”

“Yes,” Ajay said cautiously, then added, trying to sound firm, “But ownership doesn’t override human dignity. I mean, not in a functioning democracy.”

The man squinted. “You a politician?”

“No. I’m a kid. But my family is from Mumbai. Most of my cousins still live in slums.”

The man nodded slowly. “So you’re one of us, then.”

Ajay didn’t answer. He felt something tighten in his chest—not fear exactly, but a kind of awareness. A shrinking and expanding, all at once.

Nunzio reappeared in the lobby, tipping his cap again. “See what I mean? Fourteenth floor’s a mess. But they’ve got a point, too. This place has history. You’re walking a fine line. You let the squatters stay, you’ll have a rent mutiny on your hands. You kick them out, you’ll be painted as heartless. You bought yourself a real problem when you bought this building, kid.”

Ajay stepped closer. The high-rise was now shoulder height. He could see into the windows with ease—arguments, laughter, desperation—all flickering in miniature, repeating in rooms no bigger than matchboxes.

He crouched, eyes level with the fourteenth floor. The man had disappeared back inside.

Ajay whispered, “What am I supposed to do with all of you?”

The building didn’t answer.

The next morning, Ajay sat at the breakfast table, staring into a bowl of cereal gone soft. His father scrolled through headlines on his tablet, one hand nursing a mug of black coffee. His mother moved between the toaster and her inbox, already dressed for her first seminar.

Ajay cleared his throat.

“I might have to evict some tenants,” he said.

His father didn’t look up. “Tenants?”

“In my building.”

Now his father glanced over the rim of his glasses. “Ah, the imaginary high-rise again.”

Ajay didn’t answer.

“Well,” his father said, setting down his mug, “evictions are never a clean solution. You want to clear space, you get a mess. Legally, morally. Best case, you write a letter. Worst case, you get sued.”

“Dad, it’s complicated. Some of them don’t have anywhere else to go.”

“They never do,” his father said, not unkindly. “But you also can’t have a building overrun with squatters. You let them stay, and next thing you know, everyone stops paying rent.”

His mother chimed in from behind her screen. “This is what happens when you privatize housing without social policy. Even in imagination.”

“I didn’t privatize anything,” Ajay muttered. “I bought it for seven dollars.”

His father raised an eyebrow. “Seven dollars? That’s quite the acquisition. Well, you could always put it back on the market.”

Ajay gave a tight smile. He could feel them drifting already, back into their work, their routines, their analysis.

“Well, good luck, beta,” his mother added, glancing at her watch. “Don’t let the rent control laws scare you.”

“Thanks,” Ajay said quietly.

They returned to their screens. The subject was closed.

Ajay sat a while longer, letting the cereal turn to paste. Then he got up, walked back to his room, and closed the door behind him.

The building had grown to six feet in height. Ajay gasped at the sight of it. The windows flickered dimly in the soft morning light, the air in the room unusually still, as though holding its breath.

And then he saw her.

The woman in 22C.

She stood on a narrow ledge outside a window on the twenty-second floor. Her toes curled over the edge, her arms crossed against the wind, which Ajay couldn't feel but somehow knew was cold. She was barefoot. Her hair clung to her face. She looked smaller now, a collapsed version of the figure he’d once glimpsed pacing behind glass.

Ajay pressed his face close to the building.

“Hey, you!” he said, his voice cracking.

She didn’t move.

“I see you!”

Her head turned slowly. Her eyes were empty.

“You shouldn’t be able to,” she said.

“What are you doing?!”

The woman in 22C looked back out over the city. “I don’t want to be here anymore.”

Ajay swallowed hard. His heart was thudding against his ribs. “Please. Don’t jump.”

“What are you? And why are you talking to me? You don’t know anything about me! I'm going to do what I believe I have to do! I’m finished with this city! And I don’t want to live anymore!”

Ajay hesitated. He wanted to answer as his parents would have—calm, logical, maybe with a reference to statistics on suicide rates. But something inside him wouldn’t allow it.

“I know what it’s like to feel alone,” he said. “Like there’s no place that fits, even in your own home.”

The woman in 22C didn’t speak.

Ajay continued, words pouring out now. “I know what it’s like to watch people talk about justice and belonging and never once ask you how your day was. I know how quiet can feel like a punishment. I know what it’s like to disappear in plain sight.”

She looked at him again. Her lip trembled.

“I came here when I was nineteen,” she said softly. “I had dreams. I was going to dance at Lincoln Center. I told everyone back home in Jaipur that I’d be on stage by twenty-three. That was eight years ago. Now I clean apartments and wait tables and sleep on couches I don’t own.”

“What is your name?” Ajay said.

“Mina.”

“I’m Ajay. You said you were from Jaipur. I’m from India too. Mumbai!”

“I’m thirty-one, Ajay,” Mina whispered. “Too old for ballet. Too scared to go home to Jaipur. I don’t want to be a failure.”

Ajay felt tears rising, uninvited. “You’re not.”

“How would you know?”

“I don’t,” he admitted. “But I know you’re still here. That has to mean something.”

Ajay’s fingers were hovering near the window. “You’re very pretty, Mina,” he said, the words awkward, but earnest. “I mean, not just how you look. But you gave it everything you had for eight years.”

She said nothing. She looked down.

Ajay pressed on. “In Mumbai, where my parents are from, there’s this story my grandmother used to tell about a woman who wandered through a forest looking for God to save her. She kept walking, even after she lost her shoes, even after her voice gave out. But in the end, God didn’t save her. But all was not lost! She found a river, and the river saved her.”

“How so?”

“Because she saw herself in it. She realized she was never looking for God. She was looking for a reflection that would speak back.”

Mina blinked. Her shoulders relaxed slightly.

“You don’t need to jump,” Ajay said. “Maybe I’m the reflection meant to speak back to you!”

Her foot inched backward, off the ledge. And all of a sudden, she let out a cry, “No, no, no, you don’t understand.”

Ajay held his breath.

Mina leaped from the ledge of the building.

Ajay’s hand shot forward, not out of thought, but instinct. His palm hovered beneath her as she fell, in a fraction of a second that stretched impossibly wide.

She was in the air, suspended.

Not falling.

Not flying.

Caught.

She landed in his open palm. Her eyes were wide, her arms clenched around herself. Her knees buckled as if she had truly fallen from twenty-two stories, and yet, she was safe. In his hand. Real.

Ajay couldn’t move. He stared at her, stunned by her weightlessness, by the heat she gave off like a tiny flame, by the shimmer of life in her eyes. His room had fallen silent. Even the usual hum of the city outside seemed to bow to this impossible moment.

She looked up at him, barely whispering, “You caught me.”

He nodded. Tears were blurring his vision now. “You jumped.”

“I didn’t think anyone would be there to stop me.”

Ajay swallowed. “Neither did I.”

They stayed like that for what felt like forever and no time at all. Somewhere in the folds of that silence, something shifted in Ajay. Not what his parents measured in grades or good behavior, but something more profound: the knowledge that every person carries a story you can’t see unless you listen hard enough.

He lowered his hand gently, placing Mina back by the twenty-second-floor window. She stood, still shaken, but steadier now. She looked at him one last time, nodded once, then disappeared.

The skyscraper pulsed with light, then dimmed.

The next morning, Ajay woke to another noticeable change in the size of his skyscraper, but he was distracted by the sound of his parents’ voices coming from the kitchen. Ajay’s mother sat at the end of the dining table, cross-legged, scrolling through The Times on her tablet. His father, still in his house slippers, sipped tea and scanned a news alert on his phone.

“Agit,” his mother called out. “A young Indian woman jumped from a building in Midtown last night. Survived the fall.”

His father glanced up. “What a coincidence. I’m just reading that now. My God!”

“From Jaipur. Attempted suicide.”

“Oh, how sad! Came to New York for ballet, the report said. Miraculously, she survived.”

“Yes. She landed on scaffolding—bruised ribs, broken leg, but alive.”

At that moment, Ajay entered the room and quietly took his seat at the table. No one noticed at first. He poured cereal into a chipped bowl and added milk that smelled faintly of the fridge. He listened.

Ajay’s father shook his head. “So many come with that dream: writers, poets, artists, dancers. Their life is brutal. No safety net.”

Ajay looked up. “Do you think it’s real?”

His parents glanced at him.

“The story,” he said. “About the ballerina. How do you know it’s real?”

His mother blinked. “Because it’s in the news, beta. There’s a photograph.”

“Sometimes they get things wrong,” his father said. “But yes, it’s real enough.”

Ajay looked down into his cereal. “It just doesn’t feel like it.”

“You mean because it’s sad?” his mother asked.

Ajay didn’t answer.

His father leaned back. “She came from India, Ajay. Like us. That part of it is real, too.”

“We’re different,” his mother added. “She came with her body. We came with our minds.”

“Do you think God saved her?” Ajay suddenly asked.

“God? Your grandmother would say so,” his mother said, taking a bite of toast. “God or no God, anyone who attempts suicide is irrational in their mind.”

“Yes, well, ballerinas are light as a feather,” his father said. “Maybe that’s what saved her.”

The news moved on. His mother tapped at her tablet. His father stirred sugar into his tea.

After a quiet moment, his father looked over the rim of his mug. “So,” he said, “how are things going with your skyscraper? Settled the squatters’ issue?”

Ajay swallowed a spoonful of cereal. “The building shrunk.”

“Shrank,” his mother corrected gently. “Proper English, beta.”

“Shrank,” he repeated. “Back to six inches. Just like when I bought it.”

His father chuckled. “Guess your zoning board finally passed those regulations.”

“Or maybe your tenants unionized,” his mother said, smiling faintly.

Ajay smiled too, but distantly. He looked out the window. The skyline glinted in the sun. It was quiet again.

“Well,” his father said, “your birthday’s right around the corner, Ajay. Isn’t it? Twelve going on thirteen. You’ll be a young man. Your mother and I are very proud of you.”

“You’ll have to trade in your six-inch skyscraper for a job application,” his mother added, then smiled. “Or better yet, an entrance essay.”

His father sipped his tea, then added, more to himself, “Yes, something about your skyscraper. No matter how small or tall, it’s the shadow it casts. That’s not the first thing people notice about a skyscraper. The shadow it casts.”

Ajay looked down at his hands. Then at his parents.

“Maybe it’s because as the sun moves, so does the shadow,” he said.

“Yes, I think you’re on to something, Ajay.”

© Michael Arturo, 2025

Michael Arturo is a playwright, screenwriter, and fiction author who also writes random essays on social and political issues. He was born and raised in New York City. His plays have been produced in New York, London, Boston, and LA. He also created the Double Espresso Web Series from 2010 to 2014. Vimeo.com/espressodes

To support his work, please donate, purchase a subscription, leave a comment, or follow. Thank you.

Buy Me A Coffee

Support by hitting the like button or leaving a comment.

Share this post