(“Skyline” was a Top in Fiction’s selection for the month of February, 2025)

Elliot Van Alen leaned against the window of his Park Avenue apartment; his forehead pressed to the cold glass. Fifty-four stories below, the city churned—a grid of relentless motion, lights flickering like neurons firing in the collective brain of Manhattan.

But tonight, the view offered no solace. Where he once saw triumphs of steel and ambition, he now saw a fractured landscape, its gleaming towers reduced to crumbling blocks in his mind. His thoughts were fixated on the building he’d spent the last year designing, a sleek, modern tower meant to crown the Midtown skyline. It had been rejected that morning, dismissed with a single, devastating word.

“Derivative,” the client had said, his voice thin with the brittle authority of disappointment. “We wanted something timeless, and this… well, it just isn’t it.”

Elliot hadn’t argued. He’d learned there was no point. Once the industry branded you a has-been, you became invisible—your ideas, no matter how bold or beautiful, drowned out by the hum of younger voices. At forty-three, he was in freefall; his last two projects were scrapped, and his name was whispered with pity at gala dinners.

He closed his eyes and tried to summon a sense of direction, but his thoughts spiraled instead, circling the same nagging truth: maybe they were right. Maybe his best ideas were behind him.

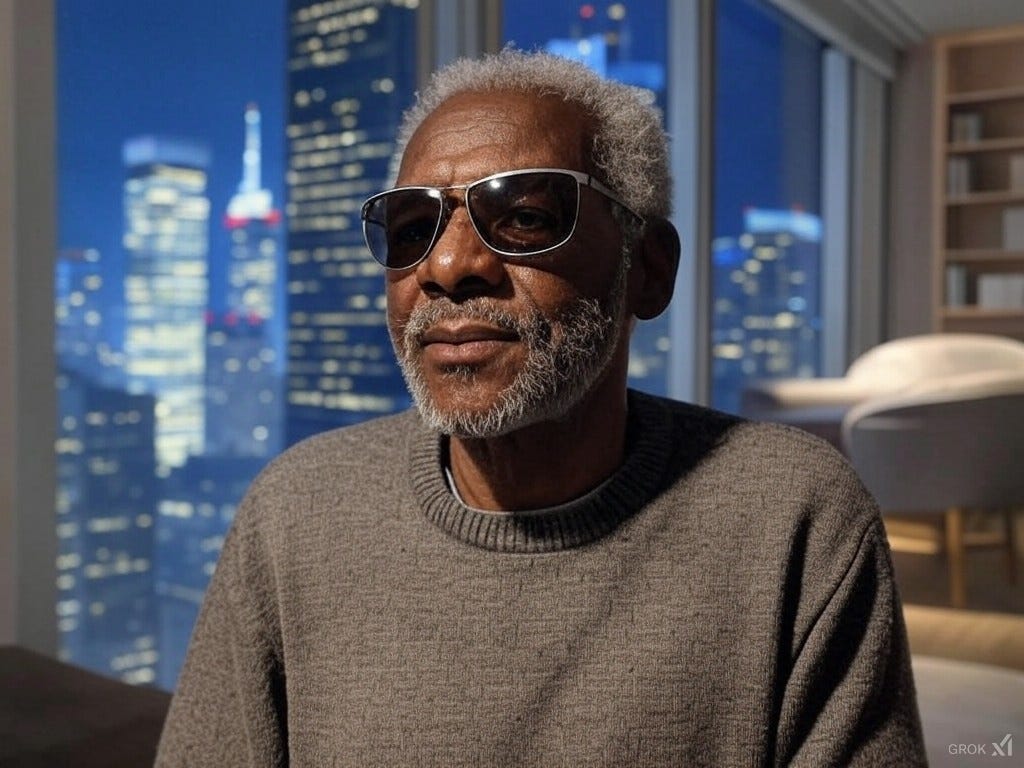

That was when he found Solomon—hunched by the subway grate across the street. He was wrapped in a battered coat; his head tilted slightly upward as though he were listening to the city.

Elliot didn’t know what made him go down there. He didn’t have a history of gestures like that and didn’t drop coins in guitar cases or pause at the sight of cardboard signs. But something about the man held him. Perhaps it was the contrast between his blind eyes, clouded and searching, and the oddly serene expression on his face.

“You need help?” Elliot asked, shoving his hands deep into the pockets of his overcoat.

Solomon turned his head slightly. “Don’t we all?”

Elliot laughed, a sharp, tired sound. “Fair enough. I’m serious, though. What do you need?”

“Coffee would be nice.” Soloman’s voice was gravelly, but there was a lilt to it, almost like a song.

They ended up at the diner around the corner, seated across from each other in a booth. Elliot ordered pancakes and eggs for the man, who introduced himself as Solomon. The name suited him, Elliot thought, regal and ancient.

“You live around here?” Solomon asked, running his fingers lightly over the rim of his coffee cup.

“Park Avenue,” Elliot said, then immediately regretted it. Solomon gave a low chuckle.

“Must be nice,” he said.

“It’s alright,” Elliot replied. He felt ridiculous, sitting in his tailored coat, trying to converse with someone whose life he couldn’t begin to imagine.

But then Solomon said something that stopped him.

“This city,” he murmured, “it’s always talking if you know how to listen. The hum of it, the way the sounds stack on each other, like a rhythm. It’s all structure, you know? A kind of architecture.”

Elliot stared at him. “Architecture,” he repeated.

“Sure. Everything has a shape. Even sound.” Solomon tapped his fingers against the table's edge, a staccato beat. “I might be blind but I can see. If you know what I mean,” Solomon chuckled.

Elliot shifted on his seat, and Solomon sat quietly for the moment, his blind eyes still and unblinking, the faintest hint of a smile tugging at the corners of his mouth.

“Elliot Van Alen,” Solomon said, as though tasting the name. “That’s you, right?”

Elliot’s brow furrowed. “That’s right,” he said cautiously. “How did you know?”

“You told me,” Solomon replied.

Elliot blinked, searching his memory. “I don’t recall telling you.”

“Maybe you didn’t,” Solomon said, shrugging. “Maybe you did. Doesn’t matter.” He leaned back slightly, tilting his head. “Reason I ask is… you’re not related to the Van Alen who designed the Chrysler Building, are you?”

The air between them seemed to thicken, the question landing with a weight Elliot hadn’t expected. He leaned forward slightly, his voice low. “As a matter of fact, I am. William Van Alen was my granduncle. How did you know that?”

Solomon chuckled softly, his fingers idly tracing the edge of his coffee cup. “Everyone knows about William Van Alen. He’s a piece of the skyline. People like me, we don’t forget that kind of thing.”

“People like you?”

“People who pay attention,” Solomon said simply. “It’s all still up there, you know. The Empire State, the Chrysler, the bridges. They don’t just belong to the city; they belong to time itself. You ever think about that? The weight of it, carrying a name like Van Alen?”

Elliot’s mouth went dry. The question struck somewhere deeper than he cared to admit. He nodded stiffly. “I’ve thought about it.”

“Of course you have,” Solomon said, his smile widening just enough to unsettle. “It’s in your blood, after all. You can’t escape it, no matter how much you try.”

Elliot stared at him, the man’s words curling like smoke in his mind. “You seem to know a lot about me for someone I just met,” he said finally, his tone sharper than he intended.

“Do I?” Solomon said. “Or maybe you’re just surprised by how much of yourself you’ve given away without noticing.” He paused, letting the thought linger. “That’s the thing about names like Van Alen. They carry a lot of weight, but they’re not exactly subtle. It’s like walking around with a neon sign over your head.”

Elliot couldn’t decide whether to laugh or get up and leave. But something about Solomon, something in his deliberate calm, held him in place. “You’re an unusual guy,” Elliot said, leaning back in his chair.

“Maybe,” Solomon replied. He gestured toward the window, where the city lights blurred into streaks against the glass. “But this place? This city? It’s full of unusual people. You don’t survive here otherwise.”

Elliot studied the man, the lines etched into his face, the odd serenity in his voice. He still couldn’t explain why he’d stopped to talk to him, why he was still sitting here, and yet…

“You want to come up? Hang out, talk a bit?” Elliot heard himself say.

Solomon cocked his head slightly, as though considering. “Park Avenue? Damn!”

Elliot nodded, his voice quieter now. “Why not?”

For a moment, Solomon didn’t move, and Elliot thought he’d refuse. But then Solomon stood, sliding his chair back with a faint scrape.

“Alright,” Solomon said. “Lead the way.”

Elliot dropped a twenty on the table and rose to his feet, his pulse quickening as they stepped out into the cool night air. He told himself it was nothing, just a strange, impulsive decision to indulge a blind man’s curiosity. But deep down, he couldn’t shake the feeling that he was stepping into something much larger than himself—a vortex he couldn’t see, but that was already pulling him in.

Solomon moved cautiously about Elliot’s apartment, his fingers grazing surfaces as though reading them like Braille. He stopped at a framed piece hanging low on the wall and tilted his head.

“What’s this one?” he asked.

Elliot glanced over. “That’s Basquiat,” he said. “From his ‘SAMO’ days.”

“Basquiat.” Solomon repeated the name slowly, tasting it. “I like that. Young Brooklyn boy, right? Didn’t make it to thirty.”

Elliot nodded reflexively, then remembered and said, “Yeah. He was part of the whole ‘80s downtown scene. You know, Warhol, Keith Haring… it was chaos, but brilliant chaos. The city felt alive then. Like anything was possible.”

Solomon smiled faintly. “That’s why I came here. 1984. Back when this city still had dirt under its nails. You could smell the struggle, and the ambition.”

Elliot looked at him, intrigued. “What did you come here for?”

Solomon traced the edge of a shelf with his hand. “Music,” he said simply. “Classical, mostly. I was a pianist, back then.”

“You were?”

“Not a great one,” Solomon admitted. “But good enough to get by. I’d play gigs in little cafes and hotel lobbies, pick up session work here and there. At night, I’d go out, wander the clubs, meet people. Women.” He laughed, a low, rich sound. “There were always women.”

“Sounds like quite a life,” Elliot said.

“It was,” Solomon said, and his voice softened. He moved to the window, standing close to the glass, though his unseeing eyes stared past the city lights. “Then I lost it.”

Elliot hesitated. “How?”

Solomon leaned his forehead against the glass, as though he could feel the pulse of the city through it. “Detachment of the retina,” he said. “It started in one eye, then the other. By the time I saw a doctor, it was too late to save either. I was twenty-nine.”

Elliot felt the weight of it settle between them. “I’m sorry,” he said finally.

Solomon shrugged. “Life doesn’t care if you’re sorry.” He paused, then turned, his cloudy eyes seeming to fix on Elliot. “You ever think about what it means to lose something you love? Not just to misplace it, but to have it ripped away? Something that’s part of you?”

Elliot thought of the skyscraper that had been rejected that morning, of the hollow ache it left in his chest. But he knew better than to compare. “I’m not sure,” he admitted.

“I think about it all the time,” Solomon said. “Losing my sight meant losing the piano, losing music. I’d spent my whole life believing music was my purpose. And then, just like that…” He snapped his fingers. “Gone. I didn’t know who I was anymore. I could have learned to play blind, I suppose. But I didn’t want that. That’s the thing about losing something—it forces you to look for something else. Or someone else.”

Solomon turned toward the floor-to-ceiling window, his movements deliberate, as though he were conserving energy for something that mattered. “Mind if I check out the view from up here?” he asked. “A man of my means doesn’t get to the 54th floor very often.”

"Of course,” Elliot said, stepping closer to him. “I’ll help you. We’re looking at the best view in the city. Midtown right at our feet, Downtown further on. You can see all the way —”

“Lady Liberty in the harbor?” Solomon interrupted.

“Yes,” Elliot replied, smiling.

“Hold on,” Solomon tilted his head slightly as though listening to the skyline itself. “Let me help you. The Empire State Building should be… right about there. And over to the west…the Hudson Yards. You’ve got those new glass-and-steel giants like someone dropped ice cubes into the skyline.”

Elliot stepped closer, watching him intently.

“Your granduncle’s Chrysler Building’s further over, east side, of course. You can’t miss the spire. Stroke of genius, if you ask me. You’ve got Grand Central tucked down there, don’t you? Those train tracks running like veins under the skin of the city.”

Elliot stared at him, amazed. “How… how are you doing this? You can’t see any of it.”

“But I’ve got the map right here.” Solomon said, tapping the side of his head with two fingers. “When you’ve lived in this city long enough, it gets inside you. You know the rhythm of the streets, the way things fit together. I might not see the skyline, but I’ve walked through it a thousand times. The Empire State on 34th, Chrysler a little higher up. You go west, you hit the Hudson; east, the river and the bridges. It’s all there.”

Elliot shook his head, impressed. “Still. That’s uncanny. You’ve got the layout memorized.”

“Not memorized,” Solomon corrected. “It’s… felt. You don’t need eyes to know this city. You just have to listen to it, feel its pulse. The way the wind shifts—it’s not random, you know. It’s channeled between the buildings. The city talks to you if you let it.”

Elliot turned back to the window, looking out at the glittering expanse of Manhattan. For all the hours he’d spent staring at this view, he realized he’d never seen it the way Solomon described it: not just as a collection of towers and lights, but as something alive, breathing, stitched together by invisible threads.

“You architects build the skeletons, but the city fills them in—people, sound, stories. It’s never really yours, you know.”

Elliot looked at Solomon again, trying to imagine what it was like to navigate the world without sight, relying only on memory, intuition, and sound. He felt a pang of something he couldn’t name—admiration, maybe, or envy.

“You really don’t miss a thing, do you?” Elliot said.

“Tell me now. That building your client told you was trash. Describe it to me. I’ll help you redesign it.”

Elliot leaned against the dining table, staring at the blind man who had somehow slipped into his life and now sat before him, speaking with the quiet confidence of someone who knew things Elliot couldn’t begin to grasp. The absurdity of it struck him like a jolt—what kind of architect takes advice from a stranger who can’t even see? And yet, there was something about Solomon, about the deliberate way he spoke, his words like measured steps on uneven ground.

Elliot opened his mouth to protest, to brush off the offer as ridiculous, but the words wouldn’t come. Instead, he felt an odd pull, the same sensation that had made him stop on the street earlier that day, the same strange gravity that had brought Solomon into his apartment. Who was this man, really? A drifter? A relic of some forgotten version of New York? Or something else entirely?

“I don’t even know why I told you all that,” Elliot said finally, his voice low.

Solomon smiled faintly, his clouded eyes fixed on some unseen point beyond the room. “Maybe you’re tired of hearing your own excuses,” he said. “Now, tell me about the building. What did you want it to be before you let them talk you out of it?”

end of part one

© Michael Arturo, 2025

Buy Me A Coffee

Support by hitting the like button or leaving a comment.

Welcome to Michael’s Newsletter. Writer of contemporary political/social commentary, parodies, parables, satire. Michael was born and raised in New York City and has a background in theater and film. His plays have been staged in New York, London, Boston, and Los Angeles.

Michael also writes short literary fiction. Below is a link to his first collection.

FLATIRON and other tall tales

“‘Crosstown"

Rainspell

A lone cab sped along the wet asphalt, its reflection shimmering in the waterlogged street. Inside, Lena pressed her face to the window, watching the city blur into streaks of light—like memories she couldn’t quite hold. She had come here chasing a name, an echo of her grandfather’s whispered stories. He had spoken of the Brooklyn Bridge as if it were a…